By Bill Barnwell

By Bill Barnwell

Bill@patriotsdaily.com

At Football Outsiders, our analysis of the game goes in two different directions. The former, and the one we’re more known for, is our statistical analysis of the game using new methodologies. What we also do, though, is something else you don’t see in many other places on the net: Breakdowns of X’s and O’s, primarily by Mike Tanier in his weekly “Too Deep Zone” column on our site. Recently, Mike wrote up a “Blueprint” on how to quiet the Patriots offense, a defensive scheme with guidelines the Jaguars mostly followed on Saturday.

In that same vein, I’m going to spend this week looking at three plays from the Patriots and Chargers previous encounter, and what they show us about how the two teams match up and what they each might do to gain the advantage when the Patriots are on offense. I did not break down any plays where the Chargers were on offense because, really, it’s hard to tell what their offense is going to look like come Sunday. Chris Chambers wasn’t on the team in Week 2, while Antonio Gates, LaDainian Tomlinson, and Philip Rivers were all 100%. I’ll be using a similar style to Mike’s diagrams, which means it’s all Paint, all the time, daddy-o.

Instead, I’ll focus exclusively on three plays from when the Patriots were on offense in the game, two of which were successful.

Touchdown Pass to Watson

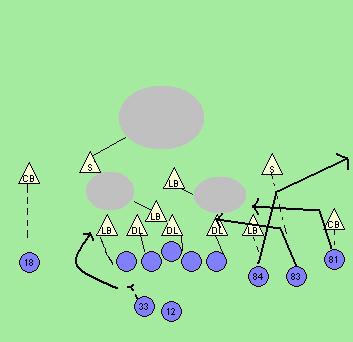

The game’s opening score came on a six-yard touchdown pass from Tom Brady to Ben Watson early in the first quarter, a play which exemplifies just how difficult it is to stop the Patriots offense. The Chargers line up in their 3-4 scheme, with the impact players being outside linebackers Shawne Merriman (lined up across from Ben Watson on the right) and Shaun Phillips (on the line of scrimmage on the left), as well as defensive tackle Jamal Williams, who warrants a double team from the Patriots in most of the snaps from this game. On this play, he’s handled by Dan Koppen and Billy Yates, who started at right guard this game. Phillips rushes and is blocked cleanly by Matt Light, but Kevin Faulk also chips Phillips coming out of the backfield before running a short curl route.

What makes the play work is the timing of the three receivers on the right, Watson, Wes Welker, and Randy Moss, from left to right. Watson is in man coverage against Merriman, who’s not a superb cover linebacker, but is fast enough to keep up with Watson, unlike most linebackers. A safety is matched up against Welker, while Moss has a corner bumping him at the line. He doesn’t get a clean break on his route and even if he did, he’d run right into Chargers inside linebacker Stephen Cooper and his zone. For those people who pretend that Moss doesn’t give up on plays anymore, he’s literally stopped and is looking around bored when the ball is thrown.

The timing of Watson and Welker, though, make the play work. As Welker runs his in, he turns just as Watson begins his cut in the corner route. Welker’s route effectively picks Merriman without touching him, and by the time Merriman can do anything about it, he’s grumbling with Cooper as Watson is about to catch the game’s opening score. The Chargers actually called a pretty good play against this pass, and they still couldn’t do anything about it. The natural response to that by a defensive coordinator is to blitz.

Merriman Sacks Brady

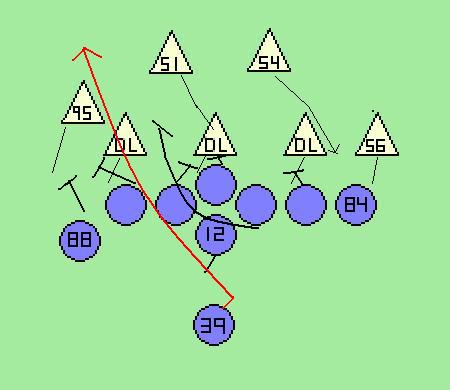

The second play is a sack of Brady by Merriman on what’s technically a blitz, but is in reality just five men rushing versus what should be seven men blocking. That’s a good scenario for the Patriots, but the failure of Laurence Maroney on the play seals Brady’s fate.

The play call is simple enough: It’s what amounts to a series of zone clearouts, with Moss occupying the safeties while Welker runs his standard in and Watson runs what appears to be another corner. The routes are approximated because they didn’t appear on the broadcast, and there are defensive players missing because they were out of camera shot. The protection is relatively straightforward, with Kyle Brady remaining in on the right side to serve as assistance on Merriman, and Maroney chipping on any penetrators before heading on his merry way into the middle of the field. Again, with only five rushers, this should be an easy blitz pickup for the Patriots.

Let’s look at the important part of the play, the interior rush, a little closer. Highlighted in red are the rushes of Cooper (54) and Merriman (56), who play the big roles in making the sack happen. The play is a series of failures by the protection, highlighted by Maroney.

At the instant of the snap, everyone knows what to do. Light handles the right defensive end (not viewable from the camera angle, but likely Igor Olshansky). Logan Mankins and Koppen double-team Williams. Yates picks up Cooper on a straight bull rush, while Nick Kaczur blocks Luis Castillo (93). Merriman drops off the line of scrimmage, so Brady helps out on Castillo.

The first failure is by Yates. Cooper’s bull rush isn’t designed to get to the passer, but instead to create a hole for Merriman’s twist to get through. Cooper succeeds, pushing Yates back three yards, and creating the diversion, in a sense, for Merriman’s blitz. The other two linebackers, Phillips and Tim Dobbins, drop into short zones so that Merriman’s rush has time to get home.

Merriman shows up with a head of steam about a half-second behind Cooper, a mess Maroney’s assigned to clean up. Instead, Maroney…kinda steps in the mess and walks away. He bumps into Merriman, but to call it a block is to give it far too much credit. It merely slightly deflects Merriman instead of blocking him, the biggest mistake on the play.

As this is going on, Kaczur realizes that Merriman is blitzing, and as a result, that Merriman was really his man to pick up, not Castillo. Kaczur then abandons Castillo in order to try and stop Merriman, but with Brady blocking Castillo from the outside at a poor angle, Castillo easily tosses the tight end aside and follows Merriman right to the quarterback. As for Kaczur, he trips over Maroney, who’s trying to get away from the scene of the crime as quickly as possible. Merriman and Castillo meet at Brady, who never has a chance to throw the ball.

This blitz is one of the things you have to do to beat the Patriots: Namely, get pressure with fewer rushers than the Patriots have blockers. 5 on 7 is normally an offensive advantage, so for the Chargers to get a sack here is a huge coup. The Patriots’ mistakes in the blocking decisions didn’t help, but this came down to the rushes of both Cooper and Merriman, the former serving his role as a de facto tackle perfectly, the latter timing his blitz well and brushing off the mediocre blocker to get to the quarterback before the wideouts can create space for themselves in the level between the short zones the linebackers are in and the deep zones the safeties occupy.

As for Maroney, his failure here is the primary reason why he doesn’t see the field as often as a first-round back with his running talent would expect: His blocking simply isn’t up to snuff. Against the Jaguars, a team with a middling pass rush, that’s not a big deal; against the Chargers, that will be a much bigger issue. Expect to see more of Kevin Faulk and Heath Evans in the backfield on Sunday, and while that will hurt the Patriots some in the running game, if their offensive line opens up holes the way they did in our final play, it won’t matter who’s back there.

Patriots Offensive Line Opens New HOV Lane for Maroney

We also focus on the interior play in this shot. The Chargers line up in what basically amounts to a 5-2 front, with Phillips and Merriman on the line and the two middle linebackers occupying the gaps inbetween the defensive linemen, several yards off. Kyle Brady rests on the hip of Matt Light, while Ben Watson is lined up directly across from Merriman.

The moment of the snap sees a similar pattern to our first two plays. Mankins and Koppen double-team Williams and occupy him from the get-go. That’s an advantage for the Chargers; even if Williams doesn’t make the play himself, that means that there’s now six defenders in the box against five Patriots blockers, giving them a chance to make a play on Maroney before he goes anywhere.

The reason Maroney gets fifteen yards is almost entirely due to two things. The first is the block that Matt Light puts on Olshansky. I drew where the block started, but not where it finished. At the point of attack, with Maroney likely to be running behind him, Matt Light didn’t just block Igor Olshansky. He got underneath him and pushed him a good three or four feet to the left, far out of the play, opening up a huge hole for Maroney to run behind.

There’s still more work to be done before Maroney can get there, though. Kyle Brady’s got a difficult job here, sealing the much-faster Phillips on the edge before he can get into the hole and make a play. Fortunately, Phillips helps out by attempting to take a route around Brady, making the tight end’s job much easier. They both end up in the trash on the left side.

Meanwhile, while the Chargers defensive line (including Merriman and Phillips) is crashing the play by attacking the gaps to their left, the two inside linebackers on the play, Cooper and Tim Dobbins, are filling in gaps to their immediate right. The idea is to fill every gap while taking advantage of the likely Williams double-team to have one of the linebackers run free and make a tackle on Maroney before he gets far. Instead, Merriman’s blocked out of the play by Watson, and Cooper and Dobbins overpursue the play based on Maroney’s first step, which directs him on a sweep behind Watson.

As the inside linebackers begin to dream about a big stop, Billy Yates is quietly pulling to the left side, creating an appetizing hole for Cooper to try and run through to make a play. Unfortunately for him, Maroney’s second step is to the left side, far away from the hole he’s already shifted his body to try and get to. By the time Maroney has the ball, Yates is beyond the line of scrimmage, emerging where Mankins started the play, and he’s blocking Dobbins, who would’ve likely made the play or at least slowed it down if he’d merely stayed in the gap he started in. Cooper, meanwhile, is so far removed from the play that by the time he catches Maroney, the Patriots rusher is in the secondary and about to be taken down by a safety following a 15-yard gain.

This is how the Patriots take advantage of teams who are looking pass on most downs. Randy Moss wasn’t in on this play, but the Patriots don’t hesitate to use Donte’ Stallworth in a similar role when Moss is off the field. Phillips and Merriman take themselves out of the play by pursuing outside lanes to the quarterback, while the counter movement by Maroney dekes the inside linebackers into overpursuit, and the excellent blocking by the offensive line and tight ends results in a huge gain on the ground.

You’re not likely to find anyone as bullish on the usage of statistics in understanding football as we are at Football Outsiders. With that being said, there are countless things that even the best statistics can’t measure, and things that even your standard-issue announcer doesn’t mention during gameplay. It’s the little things that you only pick up from close analysis, Wes Welker’s pick, Stephen Cooper’s bull rush, Matt Light’s blocking sled impression. The Patriots are great at a lot of the big, obvious things, but to make it to the Super Bowl, they’ll need to win a lot of the smaller, subtler battles as well.

That is really good analysis. I just hope the Randy Moss situation won’t be a distraction to the point of causing poor execution.

LikeLike

I really like the effort. Just a few quibbles.

First, the Jags really didn’t do much of anything like Tanier’s blueprint. I liked that article and I like this one, but I think you might be trying a little too hard to take credit on that one.

Second, your criticism of Maroney on that play is dead on. However, you are making conclusions about how he will be used almost an entire season later based on that play/game. Maroney’s pass blocking and blitz recognition has improved immensely since that game, and he has seen the field on plenty of passing downs of late. Maroney was on the field quite a bit on passing downs against the Giants, who have an excellent pass rushing DL.

Other than that, I think this is a very good article.

LikeLike